In the previous chapters (found here) we have touched upon the false security in the most commonly used project methodology among traditional companies, a way of thinking that focuses on the benefits of a digitalization project, how you should organize your company for successful execution of your digitalization initiatives and why system owners are normally less efficient than Digital Product Owners when it comes to improving processes.

Now, however, it is time to dive into some of the tools to our disposal when working in an agile way. As previously stated in this series, agile is more of a framework and mindset than a fixed set of rules, so there are different flavors to how it is implemented. However, the below article should give you a good grasp of where to start and how to carry carry out an “agilization” of your company.

This is a rather long article so take your time. And one more thing, I do not take credit for all the images below. If someone wants me to remove them, please reach out.

Whats all the fuzz about?

Agile methodologies take human nature and a changing world into account and eliminates a large part of documentation and steering in favor of faster development cycles. This means that we can easily adapt our road-map (will be discussed in the next article) to fit the changing strategies, plans and needs of a company that needs to move and adapt quickly.

It also relies heavily on good stakeholder managers with the ear to the ground and information available to make data driven decisions about priorities. It is thereby extremely important for companies that want to try this methodology to remove the hierarchies around the Product Owner, so that decisions can be taken in the product team itself, without having to rely on steering groups etc., simply because steering groups in correctly run agile projects should not exist. At least not in the form we are used to from waterfall methodologies.

One way, commonly used to describe the differences between Waterfall and Agile projects is the image below:

The upper row, where the car is assembled step by step, and it is only after the completion of the project that we have a useful product, is the Waterfall Model.

The second row tries to visualize that in agile projects we deliver some functionality already from the beginning of the project. This functionality is then refined, and through iterations we increase the usability of the product we are building (product in the context of Agile is the functionality we are to deliver). This means we are faster to get, at least some, functionality out, which means we can prioritize the functionality most crucial for the company and get that through the door quickly. Hence, delivering value earlier in the development cycle, than in more classic project methodologies.

Double Diamond

Since we chop up work in smaller packages, we decrease the time spent on initial pre-studies. Instead we use a model called Double Diamond, that was developed by British Design Council in 2005. We will discuss this model and how it is used through the course of a project in the section ”Initiative Boards and Alignment” below. Graphically it is usually defined like this:

How do we steer projects in an agile environment?

Instead of strict project hierarchies and procedures such as Project Managers, Steering Groups, Change Management Processes etc., the agile methodology relies on collaboration and alignment.

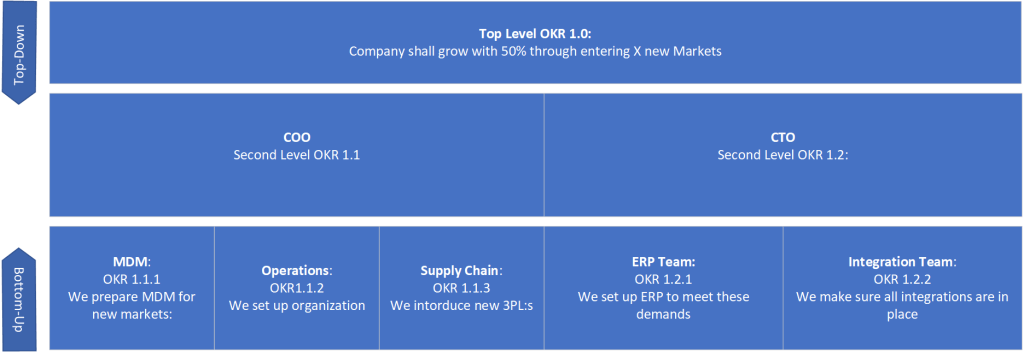

In order for all interconnected projects to march together, in the same direction and with the same purpose in mind, we use a top-down-bottom-up approach for companywide planning, where the hierarchies/reporting lines in the company are used to set a kind of structure.

This means that the upper management still steer the direction of the company and the priorities we need to have, in order to achieve the goals on short, mid and long term. However; they do not go into details with micro management as a result. Upper management thereby loses some of the detailed control, which can be scary for people who do not fully trust their employees…

At the same time, it is up to the Product Teams to set their own priorities within the framework provided top-down, so that each and every part of the company contributes to reach the goals set by the board, CEO or other decision makers.

So how is this done? Well, we have a tool for this too; OKRs.

Steering through OKRs

In order to get the various products/projects to work towards the same, higher level goals, we work with OKRs which stand for Organizational Key Results and a way visualize this is the following:

This is highly simplified view since, at least on the third level, there will be more activities and hence more OKRs. There may of course also be more levels between the Top Level and the Product Teams, which would make the above grid more granular.

The OKRs are also measurable where each one of the OKRs shall have a kind of KPIs.

As an example:

| OKR 1.1.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| We prepare MDM for new Markets | Structure is in place | Structure and data are in place | Structure, data and workflows are in place |

The above grid is used to measure the success of each workstream and brings accountability to the team responsible. It is important to realize that achieving 1.0 during the timespan for the OKR realization (usually 3 or 6 months) should be a real stretch. Landing on 0.7 is our goal.

The reason for this is to see if we over or underestimate the complexity of the tasks and that serves as a learning for the organization. With this methodology we see how efficient we are, how well we perform, and it gives accountability for each team striving to reach the higher goals of the company.

Since there will, undoubtedly, be dependencies between different teams, alignment is needed. However, this can happen in smaller circles than “big bang projects” and is thereby usually a more efficient way of working, which gives higher chances of success.

Another effect of this structure is that we are forced to focus on the things that gives most value. If we are to achieve the higher goals of the company, each contributing body, needs to make data driven decisions based on what the effect of each OKR will give us.

Initiatives, Epics and User Stories

So, without a clear Gantt chart, with clear responsibilities, visible relations between work streams and toll gates and deadlines, how do we know what to do?

In a sense we do the planning the same way as in a waterfall project, but we do it to a much more granular level.

You can compare the work streams/tasks in a Gantt chart, with what we call Epics in most agile methodologies. The Epics are then broken down in even smaller parts, called User Stories (and they can be broken down even further into Tasks)

Hence; In order to structure a project or product we use a hierarchy of building blocks.

If we use the allegory of the car in the previous segment of this article we can picture them like this:

As you can see the User Stories are not in any particular order. It is up to the product Owner to prioritize them so that they are done in order of importance for the product and hence for the company. We therefore take the effect each building block will have in terms of functionality, efficiency or whatever the purpose of the project is as an indication of what to do first in each sprint (a sprint is normally a 2 week development cycle with a clear sprint goal).

I would recommend that a company who wants to go agile, starts the transformation by introducing working with Initiatives, Epics and User Stories as a first step. And to place them on a Stand-Up Board (more about that below).

How to write a User Story

Initiatives and Epics can be written basically any way you want. The magic happens with the User Stories.

A User Story shall be written in such a way that the Who, What and Why discussed in Part 2 of this series, are clearly defined. Hence, there is a structure to how they are written, and the structure is the following:

“As a/an [WHO] I need/want [WHAT], so that [WHY]”.

| EXAMPLE: “As a visitor to the web site, I want to be able to contact the company, so that I can get answers to my questions“ |

This way to describe what is needed gives us a lot of benefits:

- We know who our stakeholder/customer is for this specific User Story

- We know what is needed in terms of functionality

- We know what the business value is for the User Story

But how do we know what to do? The above doesn’t say if this contact should happen through a form, or if we only need to publish a phone number on the web site.

Well, we have tools for this too, and this tool is very often forgotten by newbies in Agile; Acceptance Criteria.

A User Story shall not only tell what is needed, but also inform the developers about what the minimum requirements are, for a delivery to be accepted. Hence we add this to the above example:

| EXAMPLE: “As a visitor to the web site, I want to be able to contact the company, so that I can get answers to my questions“ Acceptance Criteria: – The contact form should include the following fields: Name, Email, Message, Phone Number – The fields Name, Email and Message are mandatory to fill in – The email should be checked for validity – When the user presses “Send” an email with the content in the form should be sent to our customer service team |

Now the User Story is complete, and the developers know what is needed for this User Story to be accepted by the stakeholders, once it has been completed.

How do we know what is being done?

Since we want an open and collaborative environment we use whiteboards (or any wall to your disposal) for this.

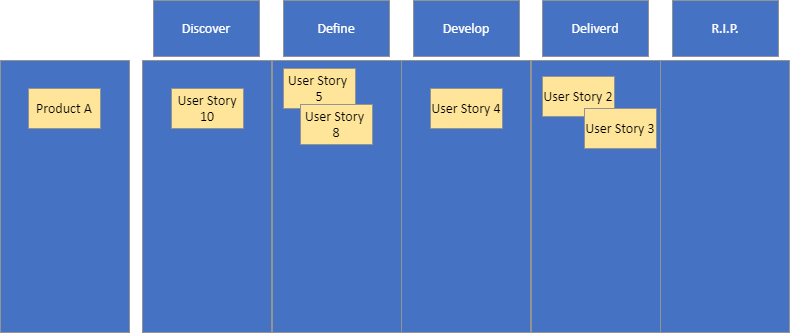

Remember the Double Diamond discussed in this article? That is the cycle each user story needs to go through, as well!

Hence we set up a board with a design that reflects this:

These boards should be designed to fit the purpose of the team, so the above design can be modified, and and you can also introduce multible horizontal work streams. These boards are usually called Kanban boards or Stand-Up Boards.

The reason to call them Stand-Up Boards, is that each team should have daily Stand-Up by this board. This is a crucial element in Agile and we use these 15 minutes to discuss today’s work, what everyone is working on for the moment, and what has been done the day before. We also mark User Stories that are blocked for some reason (this means that we, for some reason, are unable to work on it, possibly because of dependencies with other teams).

Each member of the team is working on one or more stories, and we typically place magnets with the name or picture of the team member on the corresponding stories so that everyone who is doing what.

I would recommend any company that wants to go agile, to introduce these boards first thing. It is a small step but will show the benefits and give more transparency to the projects that are ongoing.

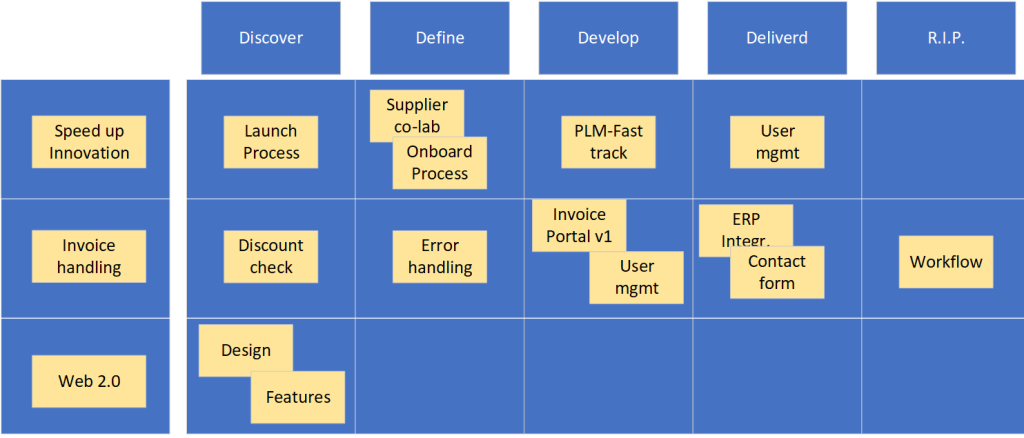

Initiative Boards and Alignment

So how do we align the work between different teams with dependencies? One way is to visit the Stand-Ups of the other teams to be informed and to align. For good visibility and alignment, it is also recommended to work with Initiative Boards that collects all the ongoing Initiatives and their Epics, across teams.

An initiative board is basically a higher-level view of a Kanban Board/Stand-Up Board, and is a way for various projects/products to align and create visibility to the ongoing initiatives. As described, a Kanban board handles User Stories which in theory are the smallest building blocks of one project/product (larger chinks can also be handled here, but lets stick with this definition for now).

An Initiative Board handles Epics or even full Initiatives for several projects/products

This board should also serve as a meeting point in the end of each sprint so that all surrounding projects and stakeholders are informed about the progress of each project/domain/initiative, and so that alignment can happen naturally between the product teams.

Schematically they look like this, and gives a good overview of progress and blockers can be handled across teams:

As you can see the board follows the structure of double diamond and the Stand-Up Boards, described above.

5 thoughts on “Part 5: The Agile Toolbox 101”